#Florence is getting supercharged by near-record warm (~2C/3.6F above normal) subtropical North Atlantic ocean surface temperatures ( ). Florence’s intensity is directly fed by the extra-warm waters of the Atlantic (as high as 86 F), which acts like jet fuel for the storm. (For more on the relationship between climate change and hurricanes, see climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe’s excellent video). No, climate change does not cause hurricanes. It is a manufactured catastrophe, a product of choices we have made about how we live, where we live and how we think (or don’t think) about our future.įor one thing, our 150-year fossil-fuel binge, which has superheated the atmosphere, has amped up the energy and intensity of big storms like Florence. (In Hurricane Sandy, 19 percent of the 106 deaths were from falling trees.)īut Florence is not simply a natural disaster. And as meteorologist Marshall Shepard points out, the saturated ground means lots of falling trees.

This is a hidden and under-reported risk: One in four hurricane deaths is from freshwater flooding. That means massive inland flooding that can extend hundreds of miles from the center of the storm. Right now, meteorologists see the storm hitting the coast, then stalling over land, possibly for as long as four or five days, and dumping huge amounts of rainfall, up to 30 or 40 inches, affecting a much wider area than the center of the hurricane itself. (Other hurricane-prone areas, like southern Florida, have a steeper slope offshore, and typically see lower surge amounts.) A surge of 15 to 20 feet or higher could sweep over barrier islands on the Outer Banks and reshape the coastline.īut inland rainfall is likely to be equally damaging. As Andrew Freedman at Axios points out, the Carolinas are uniquely vulnerable to storm-surge flooding because the continental shelf extends far offshore, by about 50 miles, creating a large shallow area that enables a storm to build up water to great heights. With Florence, the angle of approach is coming straight in at 90 degrees, which will push a big wall of water in front of it. Hurricanes push a lot of water in front of them as they spin along. But like Hurricane Harvey, which caused massive flooding in Houston last year, water is likely to be more deadly and destructive than the wind. On cable networks, you will see a lot of images of bent-over trees and reporters standing in 100-mph-plus winds and houses with their roofs blown off. Welcome to life on our superheated planet.Įvery hurricane, like every snowflake, is unique, driven by a particular mix of ocean temperature and atmospheric circulation patterns, among other things. And Florence is just one of three big storms that are spinning simultaneously in the Atlantic, at what is historically the peak of hurricane season. This is a monster storm, and it will likely have a devastating impact on the people who live in the region. Already 1.5 million people have been evacuated from the Carolina coast, and surely more evacuation orders are to come. history, with winds that are expected to accelerate to 155 mph and a storm surge up to 15 or 20 feet.

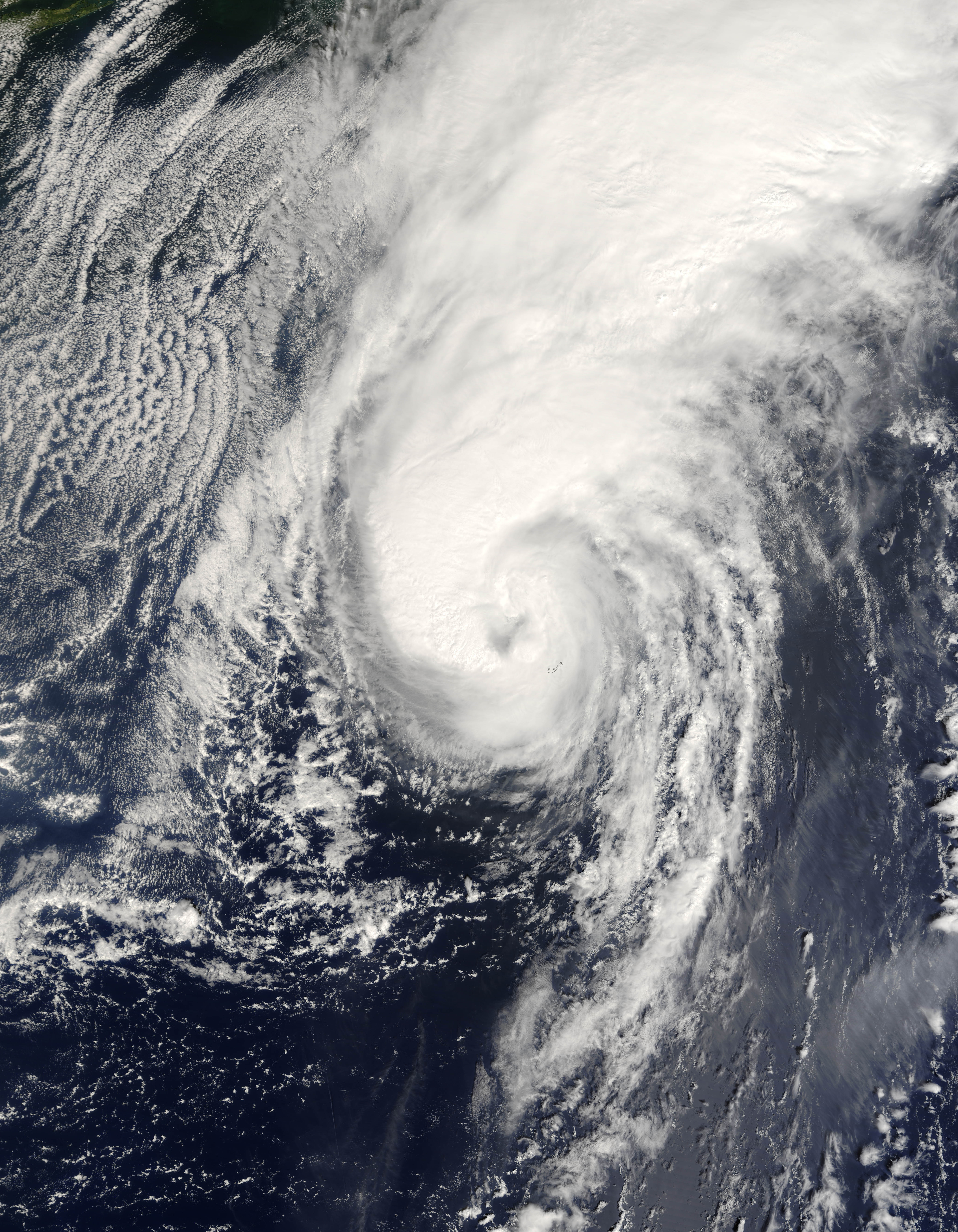

Hurricanes are fickle and can shapeshift at the last minute, but Florence is on track to be one of the biggest hurricanes in U.S. Right now, Hurricane Florence is spinning toward the mid-Atlantic coast like a giant thermo-aquatic buzz saw.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)